The Joy Of Typed Python

If I am to start working on a new project today, I would hesitate to attempt it in a language that does not have compile-time type checking. However, I do have to deal with Python at work (though we are slowly phasing it out). Also, I have been working off and on, in my spare time, on a Python project that has over the past 3+ years gotten fairly large as personal projects go. It started out as a one-off quick script. It eventually evolved into something larger that actually does something useful for me so I ended up adding to it and maintaining it.

Somewhere over a year and a half back, after being frustrated with my inability to refactor this code like I can with other type safe languages, I started exploring the possibility of adding type hints to the codebase. Now, after having spent the requisite time to understand the implications of type hinting, and whether it’s useful, and to be able to show this as a consolidation of my thoughts on the matter to friends and colleagues, I decided to write this post on what an absolute joy it has become to refactor and work with Python once you have type checking enforced.

Just to set expectations right: the following is more of gushing praise for mypy rather than a tutorial on how to use it. If you are already using mypy on a regular basis, you are likely going to learn little from what follows. This is written with the hope of giving other friends of mine who are Python programmers an overview of starting with type annotations, if they aren’t already using them by detailing the nice things it provides. It also details some of the effort you will likely need to pay up front to make type-checking effective in your codebase, and the rough edges (yes, there are some) in the type annotation system that will likely cause you some annoyance.

Another expectation I’d like to calibrate is for people coming to this from a language with a sophisticated type system such as Rust or Haskell, or even more traditional type systems like Java and C++. These are things you take for granted and you will likely scoff at some of the things written here. However, I urge you to look at the benefits the following provide to the current state of Python programming that has no static type checking.

Overview of Type Annotations in Python

First things first: Python, back from versions 3.5+, has already had support for type annotations. It is detailed in PEP 484. This means that you can write functions that look like this:

def sum(a: int, b: int) -> int:

return a + b

However, the Python interpreter in no way enforces it, and will not enforce it in future. Python is expected to remain a dynamically typed language for the foreseeable future. The above function will run happily if called with sum("hello", "world") and return a concatenation of the two strings contrary to the intended use of the function. The Python interpreter simply ignores the type annotations.

However, you can use third party type checkers which will do static analysis of your code based on these type annotations and point out any type errors lurking in your code. The introduction of type annotations as part of the language syntax itself provides for much better aesthetics as compared to having to retrofit the type hints via code comments (a la Flow for pre ES6 JavaScript) and better ergonomics as compared to needing a transpiler to convert a new augmented language to valid vanilla code (like Typescript does).

One such type-checker is mypy - the earliest implementation of its kind that some of the Python core team are involved in, including the venerable Guido Van Rossum. However, note thatmypy is a distinct from the Python interpreter and maintained as a separate project. You will need to download and install it separately.

Running mypy on a file containing the aforementioned invocation of the sum function above with string arguments results in the following error from the type checker:

Argument 2 to "sum" has incompatible type "str"; expected "int"

mypy is not the only type checker out there. There are other type checkers such as Pyright from Microsoft and pyre from Facebook. However, my experience with them is limited and the following notes are based on my experience with mypy exclusively.

Things I love

The trivial example that I stated above does not do justice to the sophistication that mypy brings. While you will need to grapple with installing, configuring it and running it on your code, in this section I’ll be detailing some of my favourite things it facilitates once you pay that price.

Optional Values, Strictly Enforced

If there is a single thing that you can take away from this post, it ought to be the unreasonable effectiveness of strictly checked optional values. Just this one feature has had such a dramatic improvement on my code correctness that I cannot emphasise this enough.

Errors in software arising from not checking for nulls is “a billion dollar problem” and mypy is an invaluable guard against them. The primary type annotation (type modifier in mypy terms) that helps with this is the Optional annotation. In my opinion, explicitly handling and indicating where a value can be null fosters greater code correctness as to approaches in languages like Java where any value can potentially be null.

Consider a canonical ‘customer record’ management scenario (yes, I’m unimaginative like that). Presumably, a simple customer type could be defined like so:

class Customer:

name: str

address: Optional[str]

In this type, we encode the fact that we may sometime not have the customer’s address registered in our database, into the type itself. In vanilla Python without annotations, we would have just defined it as a string with the possibility that it may be None that we need to ‘remember’ any time we used it.

To demonstrate the utility of Optional type used in conjunction with mypy, let’s look at a (slightly contrived) example of an implementation checking how far a customer resides from our store. To simplify the example, we abstract away the details of looking up a Geocoding service and code to calculate distance between two geo-coordinates.

A first iteration of this code might look like so:

# A type alias for a (lat, long) tuple

Coords = Tuple[float, float]

def geo_lookup(input_address: str) -> Optional[Coords]:

# ... snip ...

# Geocoding API lookup

# Hardcoding return for now

return (12.972442, 77.580643)

def calculate_distance_in_miles(coord1: Coords, coord2: Coords) -> float:

# ... snip ...

# Distance computation

# Hardcoding return for now

return 3.5

# WARNING: Buggy code below

def get_delivery_distance(customer: Customer, store_coords: Coords) -> float:

geo_coords: Coords = geo_lookup(customer.address) # Errors here

return calculate_distance_in_miles(geo_coords, store_coords)

Running this through mypy generates the following errors:

geo.py:18: error: Incompatible types in assignment (expression has type "Optional[Tuple[float, float]]", variable has type "Tuple[float, float]")

geo.py:18: error: Argument 1 to "geo_lookup" has incompatible type "Optional[str]"; expected "str"

As you can imagine, this is quite a lifesaver in more real world conditions. mypy just caught the error of using customer.address without checking if it is None. It also caught the bug where we are trying to assign the geo_coords value to the return from geo_lookup without accounting for the fact that it too can return None.

The corrected version of the get_delivery_distance would look like so:

def get_delivery_distance(customer: Customer, store_coords: Coords) -> Optional[float]:

if customer.address is None:

return None

geo_coords: Optional[Coords] = geo_lookup(customer.address)

if geo_coords:

return calculate_distance_in_miles(geo_coords, store_coords)

return None

In the above code, we take change the return type of get_delivery_address to account for the possibility that it may be None. Furthermore, we expressly handle both the possibility of customer.address being None as well as the return from the geocoding lookup service being None. As you see, mypy cleverly infers that you have indeed handled the None cases appropriately and hence does not throw errors in the new code.

As you can observe, this enforcement of checking for optional values cascades through your codebase and mypy is always looking over your shoulders to warn you against potential places where you have not handled them. Furthermore, it’s very cool that mypy manages to do a significant amount of type inference based on the conditional blocks, looking for checks for None. Contrast this with languages like C++ where, in code written with the equivalent std::optional calls to std::optional::value() method will happily compile, and fail at runtime throwing a bad_optional_access exception if in fact it holds only a null value.

If you are a Rust or Haskell programmer, you are at this point cringing at all the conditional checks, and missing your Either s and Maybes. There are some third party libraries that (sorta) provide these for you though I have not used these in my code.

Generics

The irony of lauding the support for generics in the type annotations of a language that is intrinsically dynamically typed is not lost on me. Nevertheless, as soon as you enter the world that is typed Python even if it’s make believe, you start needing generics. Thankfully, the support for it is quite nice.

Here is a snippet plagiarised entirely from the mypy documentation:

from typing import TypeVar, Generic

T = TypeVar('T')

class Stack(Generic[T]):

def __init__(self) -> None:

# Create an empty list with items of type T

self.items: List[T] = []

def push(self, item: T) -> None:

self.items.append(item)

def pop(self) -> T:

return self.items.pop()

def empty(self) -> bool:

return not self.items

The generic T in the snippet can be substituted with any type. However, in case you want to restrict T to be one of a limited set of types, that is possible too:

from typing import TypeVar

Numeric = TypeVar('Numeric', int, float)

Interfaces

Classic interface implementation as is standard in object oriented Python, using ABC module, just works, and it generally does not excite me much since most code I prefer to write myself is procedural.

However, thanks to the fact that Python supports static inheritance, i.e. you can define a @staticmethod as @abstract you can create contracts that classes can implement. This might sound a bit strange to people coming from Java where static inheritance is absent altogether.

Consider the following example:

from typing import List, Callable

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

class TreeNode(ABC):

"""Generic tree node"""

@abstractmethod

def parent(self) -> TreeNode:

"""Retrieve parent node"""

@abstractmethod

def children(self) -> List[TreeNode]:

"""Retrieve children"""

class TreeWalk(ABC):

"""Collection of functions to walk/search a tree"""

@classmethod

@abstractmethod

def name(cls) -> str:

"""Name to use in registry"""

@classmethod

@abstractmethod

def walk(cls, node: TreeNode, callback: Callable[[TreeNode], bool]) -> None:

"""

Walk function that walks the tree node by node

and invokes `callback` with each node as argument

the first time it encounters it.

If callback returns False, the walk is terminated.

"""

@classmethod

@abstractmethod

def last(cls, root: TreeNode) -> TreeNode:

"""

Returns last node in the tree from the walk process

"""

class DepthFirstWalk(TreeWalk):

"""Depth first search"""

@classmethod

def name(cls) -> str:

return "DEPTH_FIRST"

@classmethod

def walk(cls, node: TreeNode, callback: Callable[[TreeNode], bool]) -> None:

# -- snip --

# Implementation of walk

pass

@classmethod

def last(cls, root: TreeNode) -> TreeNode:

# -- snip --

# Implementation of last

pass

class BreadthFirstWalk(TreeWalk):

"""Breadth first walk"""

## -- snip --

I prefer organising code as shown above rather than an equivalent implementation of TreeWalk(er) with walk and last as instance methods in line with traditional Visitor pattern implementations.

My justification for this is that the above code fosters the use of pure functions, and eliminates the possibility of any TreeWalk implementation creating and retaining local state. Effectively, each TreeWalk implementation becomes a collection of pure functions.

Types themselves as First Class Citizens

What is cool is that the annotation system lets you take a class type satisfying an ABC as argument rather than just an instance. As an illustration, I can now use this in a WalkRegistry as shown below:

class WalkRegistry:

"""Registry of tree walkers"""

_register: Dict[str, Type[TreeWalk]] = {}

@classmethod

def register(cls, walk: Type[TreeWalk]) -> None:

"""Registers a walk"""

assert (

walk.name() not in cls._register

), "Another walk registered with this name"

cls._register[walk.name()] = walk

@classmethod

def retrieve(cls, name: str) -> Optional[Type[TreeWalk]]:

"""Retrieves a walk by name"""

return cls._register.get(name, None)

# Usage

WalkRegistry.register(DepthFirstWalk)

assert WalkRegistry.retrieve("DEPTH_FIRST") is not None

Note here that the argument walk to the WalkRegistry.register classmethod is a type and not a concrete instance. That type input is then stored in a dictionary (``WalkRegistry._register` in the above code). In other words, types themselves are first class citizens of the annotation system.

If you are from a Java background, you might be able to use the catch-all Class type to pass a type as argument but I am as of this writing unaware of a way to constrain that type to a particular interface as we do in this code (TreeWalk). In C++, as far as I know, this sort of code where you store a type in std::map is not possible at all.

I suppose this is one of the few unintended benefits of mixing a dynamically typed language with static type checking.

Rough Edges (Things that could be better)

As you can imagine, there are some rough edges you are likely going to encounter with this retrofitting of type safety into what is essentially a dynamically typed language.

Typeshed and External libraries

The first and most obvious annoyance you are likely to run into is that not all existing third party libraries will have support for type annotations already. There exists an ongoing effort called typeshed that acts a collection for type hint ‘stubs’ for major projects and is bundled with mypy. You should be able to find some of the popular libraries there (like Flask). Some of the other big libraries like numpy host the type stubs as part of the core project repository. Type stubs for other big libraries can be found maintained separately. Then again, you might be using a library whose primary author is principally opposed to type-annotations. So it’s a mixed bag, really.

However, in case you are daunted by the prospect of relying on a library that does not have type stubs, the key thing to not throw the baby out with the bathwater and discard the prospect of type annotations altogether. Instead, the key point to note is that you will typically have some wrapper code around the external library you are going to use. While the code within the functions in that wrapper themselves may not be type checked, liberally using the Any type, it is still possible to make sure that the rest of your code has type integrity. The sanity that offers is well worth the ugly unchecked API boundaries/library wrappers.

Recursive Types

You are going to run into some issues with code where types reference themselves as part of their definition.

So for example, the following code will not type check correctly (yet):

Callback = Callable[[str], "Callback"]

Foo = Union[str, List["Foo"]]

Presented with the above code, mypy shows the following error:

error: Recursive types not fully supported yet, nested types replaced with "Any"

However, this code does indeed type check without issues:

class LinkedListNode:

def __init__(self) -> None:

self.next_node: LinkedListNode

def next(self) -> LinkedListNode:

return self.next_node

Errors Don’t Reference the Type Aliases

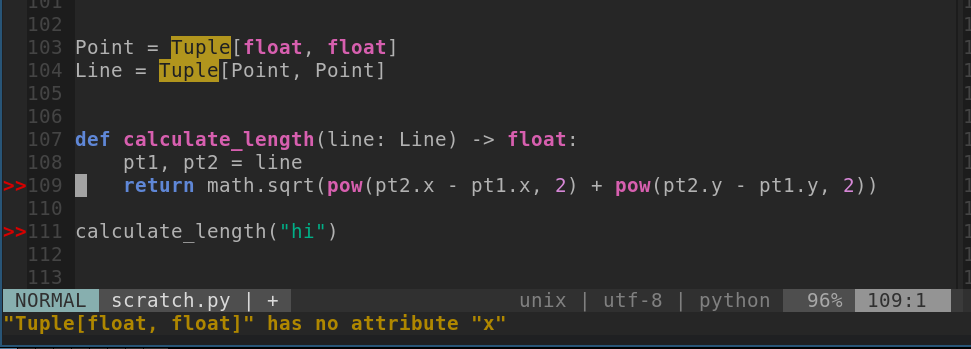

Consider the code below with an obvious type error (possibly occurring during a refactor):

Point = Tuple[float, float]

Line = Tuple[Point, Point]

def calculate_length(line: Line) -> float:

pt1, pt2 = line

# ERROR: Referencing invalid members below

return math.sqrt(pow(pt2.x - pt1.x, 2) + pow(pt2.y - pt1.y, 2))

This results in the following error from mypy

error: "Tuple[float, float]" has no attribute "x"

error: "Tuple[float, float]" has no attribute "y"

Would have been nicer if the errors actually read:

error: "Point" has no attribute "x"

error: "Point" has no attribute "y"

This might be a bit of a pet peeve and not that big an issue to most people. However, I use nested aliases significantly (as in the above code, Point being an alias for a tuple of floats, and Line being an alias for a tuple of Point) and with enough nesting the errors become a bit hard to read. For example, in the above example, were we to (incorrectly) call calculate_length("hi"), the error mypy throws is:

error: Argument 1 to "calculate_length" has incompatible type "str"; expected "Tuple[Tuple[float, float], Tuple[float, float]]"

Serialisation/Deserialisation

This is again akin to the third party code boundary issue that you can’t really enforce type safety in as nicely as you would like. For starters, there isn’t really a JSON type annotation available because that would again need recursive type support.

Furthermore, there really isn’t anything as nice as serde in Rust or marshal/unmarshal in Golang that is available here. You will need to rely on traditional Python serialisation and deserialisation facilities which work well enough, but still leaves you with the task of manually rolling custom encoders and decoders per serialisation format.

I have also had some success using a third party library like typedload to manage serialisation of simple types to and from dict , and from there onward to JSON.

Prerequisite Effort / Setting Things Up

mypy already has helpful documentation on how to incrementally introduce type hints into your existing codebase. So again, rather than providing a HOW-TO, I am going to list some the effort I had to expend to get type annotations play nice with my existing codebase.

Preliminary Refactoring - Dicts to Classes and NamedTuples

If your code relied on abstract data types like dict and list exclusively, and sparingly used classes and namedtuples, you are going to have your work cut out for you in adopting type hints. Having function types all be an inscrutable Dict[str, Any] is not going to give you the payoffs as having concrete classes. Fortunately, this kind of over-reliance on abstract data types (ADTs) vs custom types is less prevalent in Python code bases as compared to functionally written JavaScript code.

Converting a Dict to a class is no small matter and will likely see cascading changes across the codebase. This is likely going to be the most painful part of “typing” your existing Python codebase. In my case, the rewards were well worth the pain and once I had mypy run on the newly refactored code, I had lot more confidence in my code correctness.

Fighting Any Urges

As you refactor, a good rule of thumb on when to switch a dict into a class is when you start seeming to need the Dict[str, Any] annotation. Except in wrapper functions dealing with third party library code, a profusion of Any is a sure sign that you are doing typing sub-optimally.

Once you do the first type checking of your codebase, then you must strive thereafter to eschew the introduction of new uses of Any. I say strive, because the use of Any always provide a quick and dirty kludge out of a trick type resolution problem. However, the more you go down that route, the less bang for buck you’re going to get from the type annotations.

Generating Type Annotations

While I hand rolled all my type annotations, there are projects like MonkeyType which help generating type annotations by inspecting the type data collected at runtime. I reckon that even using such a project, you will need to do a once-over due diligence on your code to make sure the types generated are correct.

mypy Configuration

I spent a little time needing to tinker with the configuration file: mypy.ini setup correctly so as to tweak its default behaviour to suit my project. For eg. the mypy.ini I settled on looked like so:

[mypy]

python_version = 3.6

warn_return_any = True

warn_unused_configs = True

ignore_missing_imports = True

disallow_untyped_defs = True

disallow_incomplete_defs = True

check_untyped_defs = True

mypy_path = "myproject"

# Per-module options:

[mypy-wrappers.*]

ignore_missing_imports = False

Some salient points in the above configuration are:

- I opt in for a more strict type checking for code within my project.

disallow_untyped_defsanddisallow_incomplete_defsare invaluable here because they notify you of functions where you may have forgotten to annotate a variable or missed to specify the return type. Those things definitely take a while to become second nature when you transitioning from vanilla Python to typed Python. -

The

ignore_missing_importsin the per module configuration permits ignoring the lack of type hints of any third party modules imported in thewrappersmodule in my code, housing wrapper code around third party libraries. So assuming my code was organised like:myproject - core_stuff - tests - wrappersThen that per module configuration indicates to

mypythat any imports missing type annotations inside thewrappersmodule alone. However, I wantmypyto NOT ignore missing type annotations for imports used withincore_stuffandtests.

Customising per module configurations is a great way to incrementally introduce typing to an existing codebase. You could start off by enforcing type checks on just one core module and leave others out entirely.

Editor Integration Setup

Running mypy on the command-line manually to check for types as you keep writing code gets tedious quickly. Editor integration for mypy is fortunately easy to find and is available for most of the popular editors and IDEs. For VSCode, the Python plugin ships with mypy support out of the box. In nvim, I have mypy setup as a Python linter run by the ALE plugin. I hence get type errors highlighted for me as soon as I save the file. This quick feedback makes working in a typed Python codebase quite a joy. With proper editor integration setup, the experience coding in Python comes close to having a compiler doing this for you, that you may have come to rely on in other languages.

One point to note in this regard is that I typically also have pylint running linting checks on my code alongside mypy. This helps catch a lot of other errors which are not really type errors but helps catch bugs and improve code quality nevertheless.

Pre-Commit Hook

While having editor integration of mypy running checks on your code is great and gives quick feedback, the final source of truth is the code that gets committed. It is possible to commit the odd file in which the type correctness broke because of changes you made in an entirely different module. This will presumably be a non-issue in a company where you probably already have elaborate CI/CD pipelines to do such enforcement for you. However, my 1-man personal projects, I absolutely find it vital to run linting checks before every commit and reject those that fail those checks.

I use the excellent pre-commit library for this. I run both mypy and pylint checks in the pre-commit hooks to ensure type integrity across the project. While pre-commit library lets you run the linters on just the files containing changes in your current commit I typically run mypy on the entire project. However, in very large projects, your mileage may vary, and may be saddled with longer pre-commit lint times.

Final Thoughts

Programming with the mypy type-checker looking over your shoulder is such a dramatic improvement from doing without it, that I find it almost crippling when I have to read and modify old Python code at work that does not have type hints.

Small things like mypy pointing out that you have not handled the null return case (or more accurately, None return) correctly has saved me from what would have been hard to debug errors several times now.

To be clear, I would still not advocate writing a new service in Python. You would be much better off picking Golang, Rust or good ‘ol Java for that simply because of the performance advantages that these languages/runtimes offer over Python with their stricter type-safety guarantees. However, if you have an existing codebase already in Python that you would like to bring some sanity to, you could do worse than introducing type-hinting and slowly refactoring it.

I long for the day when someone writes for Python, an equivalent of what the Crystal (programming language) is for Ruby - a mandatory type-safe and performant successor. And when they do, PEP484 will alleviate the need to invent a new syntax.

Leave a Comment